For a piece of technology that still exists mostly in render videos and test tracks, the Hyperloop has an annoyingly persistent grip on the public imagination. Every few years, just when you think the idea has drifted into the realm of retired sci-fi concepts, it surges back with a new study, a new prototype, or a new prediction that this time we’re closer than ever.

And maybe we are. Not in the glossy “cross a continent in half an hour” sense the internet fell in love with, but in a more grounded, engineering-first way that still hints at something transformative.

A Quick Reminder of the Dream

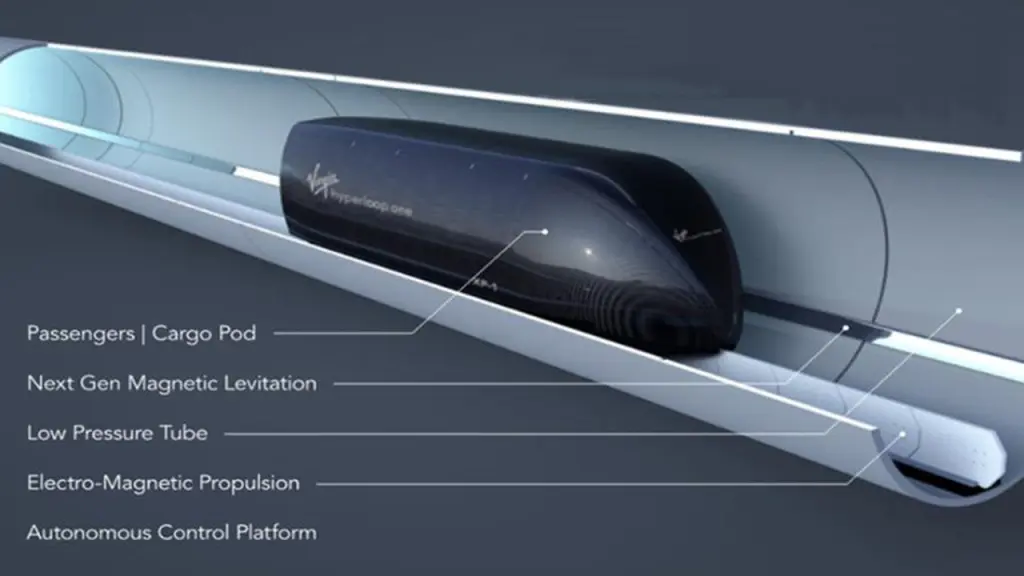

When Elon Musk published his “Hyperloop Alpha” paper in 2013, he pitched a system that sounded like the world’s fastest, smoothest rail line crossed with an aircraft’s cruising speed. The idea was simple: fire pods through sealed tubes with most of the air sucked out, eliminating drag and allowing near-supersonic travel. The pods would hover on magnetic levitation, glide with minimal friction, and—if everything went right—carry people between major cities faster, cleaner and quieter than planes.

It was bold, borderline outrageous, and completely irresistible.

What’s kept the idea alive is that, scientifically, there’s nothing impossible about it. Vacuum tubes, maglev systems and linear motors all exist. The challenge is stitching them together at continental scale without breaking budgets, politics or physics.

Where We Actually Are in 2025

A decade of hype has settled into something more measured. The high-speed renderings and wild route proposals have given way to methodical, fairly unglamorous engineering progress.

Europe, interestingly, now leads the global charge. Test sites in the Netherlands and Spain have pushed forward components like high-integrity tube segments, levitation rigs and even the first full-scale Hyperloop switch—a crucial detail that began as a trivial question on whiteboards but took years of engineering to solve. Meanwhile, the EU has spent time building regulatory frameworks rather than selling visions. It feels more like the early days of high-speed rail than the birth of a new sci-fi transport system, and that’s actually a sign of maturity.

The first operational Hyperloop lines—when they arrive—will almost certainly be for freight. Cargo doesn’t complain, doesn’t require life-support systems, and doesn’t sue if a prototype hits turbulence. Ports, logistics hubs and industrial corridors are the low-risk proving grounds. Think shipping containers, not commuters with headphones.

Passenger travel will follow only if the economics make sense. This isn’t flashy startup territory anymore—it’s infrastructure. Big, slow, expensive, political infrastructure.

The US-to-UK Idea: Ambition vs. Reality

You asked for Elon’s idea for a US-to-UK Hyperloop. And here’s the truth: while Musk never proposed a literal Hyperloop between the US and Britain, he has repeatedly spoken about ultra-long-distance, vacuum-tube travel as a theoretical possibility. The closest real-world comparison is the long-standing “transatlantic tunnel” concept—an academic exercise imagining vacuum trains running underwater between New York and London at near-supersonic speeds.

Musk, being Musk, has occasionally mused publicly about extreme-distance point-to-point travel using vacuum tubes or similar methods, often framed around the idea that once you remove air and friction, distance stops being the limiting factor.

But as an engineering reality? A submerged or seabed Hyperloop across the Atlantic would be one of the most complex construction projects in human history. Thousands of kilometres of pressure-resistant tube, unimaginable maintenance challenges, seismic risk and astronomical cost.

It’s fun to picture—imagine boarding a pod in Manhattan and stepping out in London, still warm from your coffee—but it remains firmly in speculative territory. Not impossible, simply many orders of magnitude beyond the first generation of practical Hyperloop systems.

Still, the fact that the concept lingers in conversation tells you something about the emotional pull of the idea. Hyperloop isn’t just infrastructure; it’s aspiration.

The Shift Toward Something More Real

If early Hyperloop chatter was about rewriting the rules of global travel, today’s narrative is more about solving real-world bottlenecks. Freight congestion. Port backlogs. Short-hop connections between airports and city centres.

You won’t see handheld boarding passes for vacuum-tube travel anytime soon, but you might see a cargo pod quietly shaving hours off a supply chain. And that’s how big technologies typically land—not with a futuristic bang, but with a practical foothold.

Once the hardware is proven, costs drop. Once costs drop, political risk softens. And that’s when passenger networks stop sounding far-fetched.

Why the Hyperloop Still Matters

For all the delays, cost challenges and scepticism, Hyperloop continues to matter because it represents a clean break from the “faster trains, bigger airports” mindset. It asks a deeper question: if high-speed travel didn’t require air pressure or wheels or jet fuel, how fast, efficient and connected could cities become?

The Hyperloop isn’t a promise. It’s a provocation—one that continues to push engineers, policymakers and futurists to rethink how we move across regions and continents.

If it succeeds, even in limited form, it’ll redefine expectations for speed and sustainability. If it fails, it will still have pushed high-speed transport technology further than traditional rail ever would have on its own.

Either way, the story’s not finished. The tubes aren’t built, the pods aren’t ready, and the timelines keep shifting—but the idea remains alive, humming somewhere between engineering reality and technological ambition.